- Home

- Tom Boardman

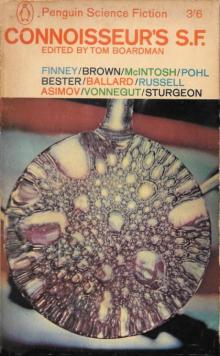

Connoisseur's SF

Connoisseur's SF Read online

Connoisseur’s

Science Fiction

An anthology edited by

Tom Boardman

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Alfred Bester: Disappearing Act

Frederik Pohl: The Wizards of Pung’s Corners

Kurt Vonnegut: Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow

Theodore Sturgeon: Mr Costello, Hero

Jack Finney: Quit Zoomin’ Those Hands Through the Air

J. G. Ballard: Build-up

Isaac Asimov: The Fun They Had

Eric Frank Russell: Diabologic

J. T. McIntosh: Made in U.S.A.

Fredric Brown: The Waveries

Acknowledgements

The following acknowledgements are gratefully made for permission to reprint copyright material:

the fun they had, by Isaac Asimov, copyright 1951 by N.E.A. Services Inc. Reprinted by permission of the author and Doubleday & Co., Inc,, from. Earth Is Room Enough.

made in u.s.a., by J. T. McIntosh, copyright 1953 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation Inc., for Galaxy Science Fiction. Reprinted by permission of the author.

diabologic, by Eric Frank Russell, copyright 1935 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction (now Analog Science Fact—Science Fiction), Reprinted by permission of the author’s agent, Laurence Pollinger Ltd.

the wizards of pung’s corners, by Frederlk Pohl, copyright 1959 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of the author and his literary agent, E. J. Carnell.

build-up, by J. G. Ballard, copyright 1960 by Nova Publications Ltd, for New Worlds Science Fiction. Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Scott. Meredith Literary Agency, Inc.

the waveries, by Fredric Brown, copyright 1943 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction (now Analog Science Fact—Science Fiction). Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s literary agent, Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc.

mr costello, hero, by Theodore Sturgeon, copyright 1953 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation, for Galaxy Science Fiction. Reprinted by permission of the author and his literary agent, E. J. Carnell.

disappearing act, by Alfred Bester, copyright 1953 by Ballantine Books Inc., for Star Science Fiction No. 2. Reprinted by permission of the author.

tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, by Kurt Vonnegut, copyright 1954 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation, for Galaxy Science Fiction. Reprinted by permission of the author and his literary agent, John Farquharson Ltd.

quit zoomin’ those hands through the air, by Jack Finney, copyright 1957 by Jack Finney, from The Third Level (Rinehart & Co. Inc.) as The Clock of Time (Eyre & Spottiswoode Ltd, 1958). Reprinted by permission of the author’s literary agent, A. D. Peters.

Introduction

To too many people science fiction still means rockets to the moon, flying through space, intergalactic wars, bug-eyed monsters, and mad scientists. Science fiction still has to live down the sensational magazine covers of twenty years ago when scantily-clad females in fishbowl helmets fought off the unwanted attentions of eight-tentacled venusians.

This anthology sets out to prove this picture wrong, to show that a great deal of original, literate, imaginative writing is being published under the soubriquet science fiction. It is also exciting and vigorous—maintaining, through the several magazines, a responsive audience for short stories of quality. While the detective story has reached a dead end, and more and more formula stories are published as the authors’ invention dries up, sf magazines offer a free market for ideas. Several established authors have turned to sf where, now, there is more freedom to write on controversial subjects than anywhere else. (In Russia this is particularly true.) Want to write about race relations? Religious prejudice? Birth control? Political ideology?—set the story in the future, or on another planet and you offend nobody officially; though the perceptive reader still gets the message.

What then is science fiction?

This question has vexed aficionados since May 1929 when Hugo Gernsback first used the term. Definitions have been coined and discarded frequently because of inadequacy. Kingsley Amis described it (in 1960) as a genre “in which speculation about the future is satire about the present in disguise, satire that covers a wide range—from politics to sex to subliminal advertising”, while it could also be put more brutally, paraphrasing Louis Armstrong on the definition of jazz—“If you’ve got to ask what it is, you’ll never know.” To my mind, science fiction (the title) is the hopelessly inadequate description of a genre which is simply any speculation about what may happen (or may have happened) to Mankind.

This collection of sf attempts to put before the reader, newcomer, or addict a selection of good stories covering a wide variety of themes, showing some of the passionate interests of science fiction authors. Broken down to essentials, each is a cri de coeur, for the sf writers are never people with tepid interests—as a group they form as opinionated a body of men and women as will be found anywhere. The authors represented here are amongst the best sf writers in English on both sides of the Atlantic. All served their apprenticeship in the sf magazines, and over the years they have helped to steer sf away from the epic of gadgetry and superficial adventure to a deeper, more meaningful, introverted approach. Science fiction of the fifties and sixties has tended towards sociological satire, examining the problems of mid twentieth century life extrapolated into the future along the lines we are going now.

But, lest this seems to be too serious, the reader will soon discover that there is one thing the stories in this collection have in common: they are told in a wryly comic, sometimes almost tragic, way. They show how conditioned we are becoming to our environment, taking for granted things that should be questioned if we are to keep a balanced attitude to life. What would happen if we suddenly lost our electric power? If we allowed our consuming habits to be dictated by advertisers? If we continue to specialize in one occupation to the exclusion of all other interests? If cities keep on expanding? If we manage, medically, to double our life span?

Each of the stories in this collection is a favourite—if you like, my personal top-ten, the only qualification being that no two stories have the same basic theme. It would be invidious to make further distinction of merit, but two stories deserve special mention. Of all topics in sf today, time-travel seems to be the least likely of being realized. (For one thing, if time travel is invented in the future, why haven’t we met anyone from the future yet?) However, it is a subject that has fascinated writers for years. In this volume Jack Finney tells with delicious humour the story of the world’s first aeroplane pilot, a private of the Union Army who flew during the American Civil War.

Theodore Sturgeon is considered by many to be the most imaginative of all writers in this essentially imaginative genre. No two stories of his are alike and in Mr Costello, Hero he introduces an unforgettable character with a terrifying penchant for bringing out the worst in our natures. Caveat lector!

In an introduction to another Penguin anthology of sf, the editor, Brian Aldiss makes the felicitous remark “Science fiction is no more written for scientists than ghost stories are written for ghosts.” If this present anthology shows anything, it shows that good sf need not even be about science. And, although the themes of these stories show sociological awareness, they are by no means tracts. I suspect they were written mainly for the enjoyment they gave the authors in working out the ideas, I am sure they will be read for the same reason. And if they do make us take another look at ourselves, our way of life, our beliefs, only those with closed minds will complain. And they will not like science fiction anyway.

TOM BOARDMAN

&nb

sp; Sunningdale, April 1964

Alfred Bester

Disappearing Act

This one wasn’t the last war or a war to end war. They called it the War for the American Dream. General Carpenter struck that note and sounded it constantly.

There are fighting generals (vital to an army), political generals (vital to an administration), and public relations generals (vital to a war). General Carpenter was a master of public relations. Forthright and Four-Square, he had ideals as high and as understandable as the mottoes on money. In the mind of America he was the army, the administration, the nation’s shield and sword and stout right arm. His ideal was the American Dream.

“We are not fighting for money, for power, or for world domination,” General Carpenter announced at the Press Association dinner.

“We are fighting solely for the American dream,” he said to the 162nd Congress.

“Our aim is not aggression or the reduction of nations to slavery,” he said at the West Point Annual Officers’ Dinner.

“We are fighting for the Meaning of civilization,” he told the San Francisco Pioneers’ Club.

“We are struggling for the Ideal of civilization; for Culture, for Poetry, for the Only Things Worth Preserving,” he said at the Chicago Wheat Pit Festival.

“This is a war for survival,” he said. “We are not fighting for ourselves, but for our Dreams; for the Better Things in. Life which must not disappear from the face of the earth.”

America fought General Carpenter asked for one hundred million men. The army was given one hundred million men. General Carpenter asked for ten thousand U-Bombs. Ten thousand U-Bombs were delivered and dropped. The enemy also dropped ten thousand U-Bombs and destroyed most of-America’s cities.

“We must dig in against the hordes of barbarism,” General Carpenter said. “Give me a thousand engineers.”

One thousand engineers were forthcoming, and a hundred cities were dug and hollowed out beneath the rubble.

“Give me five hundred sanitation experts, eight hundred traffic managers, two hundred air-conditioning experts, one hundred city managers, one thousand communication chiefs, seven hundred personnel experts…”

The list of General Carpenter’s demand for technical experts was endless. America did not know how to supply them.

“We must become a nation of experts,” General Carpenter informed the National Association of American Universities. “Every man and woman must be a specific tool for a specific job, hardened and sharpened by your training and education to win the fight for the American Dream.”

“Our Dream,” General Carpenter said at the Wall Street Bond Drive Breakfast, “is at one with the gentle Greeks of Athens, with the noble Romans of… er… Rome. It is a dream of the Better Things in Life. Of Music and Art and Poetry and Culture. Money is only a weapon to be used in the fight for this dream. Ambition is only a ladder to climb to this dream. Ability is only a tool to shape this dream.”

Wail Street applauded. General Carpenter asked for one hundred and fifty billion dollars, fifteen hundred dedicated dollar-a-year men, three thousand experts in mineralogy, petrology, mass production, chemical warfare, and air-traffic time study. They were delivered. The country was in high gear. General Carpenter had only to press a button and an expert would be delivered.

In March of a.d. 2112 the war came to a climax and the American Dream was resolved, not on any one of the seven fronts where millions of men were locked in bitter combat, not in any of the staff headquarters or any of the capitals of the warring nations, not in any of the production centres spewing forth arms and supplies, but in Ward T of the United States Army Hospital buried three hundred feet below what had once been St Albans, New York.

Ward T was something of a mystery at St Albans. Like all army hospitals, St Albans was organized with specific wards reserved for specific injuries. Right arm amputees were gathered in one ward; left arm amputees in another. Radiation burns, head injuries, eviscerations, secondary gamma poisonings, and so on were each assigned their specific location in the hospital organization. The Army Medical Corps had established nineteen classes of combat injury which included every possible kind of damage to brain and tissue. These used up letters A to S. What then, was in Ward T?

No one knew. The doors were double locked. No visitors were permitted to enter. No patients were permitted to leave. Physicians were seen to arrive and depart. Their perplexed expressions stimulated the wildest speculations but revealed nothing. The nurses who ministered to Ward T were questioned eagerly but they were close-mouthed.

There were dribs and drabs of information, unsatisfying and self-contradictory. A charwoman asserted that she had been in to clean up and there had been no one in the ward. Absolutely no one. Just two dozen beds and nothing else. Had the beds been slept in? Yes. They were rumpled, some of them. Were there signs of the ward being in use? Oh yes. Personal things on the tables and so on. But dusty, kind of. Like they hadn’t been used in a long time.

Public opinion decided it was a ghost ward. For spooks only.

But a night orderly reported passing the locked ward and hearing singing from within. What kind of singing? Foreign language, like. What language? The orderly couldn’t say. Some of the words sounded like… well, like: Cow dee on us eager tour…

Public opinion started to run a fever and decided it was an alien ward. For spies only.

St Albans enlisted the help of the kitchen staff and checked the food trays. Twenty-four trays went into Ward T three times a day. Twenty-four came out. Sometimes the returning trays were emptied. Most times they were untouched.

Public opinion built up pressure and decided that Ward T was a racket. It was an informal club for goldbricks and staff grafters who caroused within. Cow dee on us eager tour indeed!

For gossip, a hospital can put a small town sewing circle to shame with ease, but sick people are easily goaded into passion by trivia, it took just three months for idle speculation to turn into downright fury. In January, 2112, St Albans was a sound, well-run hospital. By March, 2112, St Albans was in a ferment, and the psychological unrest found its way into the official records. The percentage of recoveries fell off. Malingering set in. Petty infractions increased. Mutinies flared. There was a staff shake-up. It did no good. Ward T was inciting the patients to riot. There was another shake-up, and another, and still the unrest fumed.

The news finally reached General Carpenter’s desk through official channels.

“In our fight for the American Dream,” he said, “we must not ignore those who have already given of themselves. Send me a Hospital Administration expert.”

The expert was delivered. He could do nothing to heal St Albans. General Carpenter read the reports and fired him.

“Pity,” said General Carpenter, “is the first ingredient of civilization. Send me a Surgeon General.”

A Surgeon General was delivered. He could not break the fury of St Albans and General Carpenter broke him. But by this time Ward T was being mentioned in the dispatches.

“Send me,” General Carpenter said, “the expert in charge of Ward T.”

St Albans sent a doctor, Captain Edsel Dimmock. He was a stout young man, already bald, only three years out of medical school but with a fine record as an expert in psychotherapy. General Carpenter liked experts. He liked Dimmock. Dim-mock adored the general as the spokesman for a culture which he had been too specially trained to seek up to now, but which he hoped to enjoy after the war was won.

“Now look here, Dimmock,” General Carpenter began. “We’re all of us tools, today—hardened and sharpened to do a specific job. You know our motto: A job for everyone and everyone on the job. Somebody’s not on the job at Ward T and we’ve got to kick him out. Now, in the first place what the hell is Ward T?”

Dimmock stuttered and fumbled. Finally he explained that it was a special ward set up for special combat cases. Shock cases.

“Then you do have patients in the ward?”

“Yes

, sir. Ten women and fourteen men.”

Carpenter brandished a sheaf of reports. “Says here the St Albans patients: claim nobody’s in Ward T.”

Dimmock was shocked. That was untrue, he assured the general.

“All right, Dimmock. So you’ve got your twenty-four crocks in there. Their job’s to get well. Your job’s to cure them. What the hell’s upsetting the hospital about that?”

“W-well, sir. Perhaps it’s because we keep them locked up.”

“You keep Ward T locked?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Why?”

“To keep the patients in, General Carpenter.”

“Keep ’em in? What d’you mean? Are they trying to get out? They violent, or something?”

“No, sir. Not violent.”

“Dimmock, I don’t like your attitude. You’re acting damned sneaky and evasive. And I’ll tell you something else I don’t like. That T classification. I checked with a Filing Expert from the Medical Corps and there is no T classification. What the hell are you up to at St Albans?”

“W-well, sir… We invented the T classification. It… They… They’re rather special cases, sir. We don’t know what to do about them or how to handle them. W-We’ve been trying to keep it quiet until we’ve worked out a modus operandi, but it’s brand-new, General Carpenter. Brand-new!” Here the expert in Dimmock triumphed over discipline. “It’s sensational. It’ll make medical history, by God! It’s the biggest damned thing ever.”

“What is it, Dimmock? Be specific.”

“Well, sir, they’re shock cases. Blanked out. Almost catatonic. Very little respiration. Slow pulse. No response.”

“I’ve seen thousands of shock cases like that,” Carpenter granted. “What’s so unusual?”

“Yes, sir, so far it sounds like the standard Q or R classification. But here’s something unusual. They don’t eat and they don’t sleep.”

“Never?”

“Some of them never.”

Connoisseur's SF

Connoisseur's SF